Step 2: The Various Modus Operandi of Golf Course Architects

Key Points

Over the last 170+ years, there have been many approaches to designing and building golf courses, from “18-stakes on a Sunday afternoon”, to full design documentation being used to guide experienced or inexperienced general contractors half a world away, to computer-generated 3-D visualizations being fed into GPS-enabled construction machinery, to everything in between.

Today the three most prevalent approaches to golf course design and construction are:

a) A golf course architect is hired by the owner/developer to prepare detailed plans and specifications that are bid upon by a number of contractors and built by the selected general contractor under a separate contract (also known as Design-Bid-Build);

b) A general contractor is hired by the owner as a single point of contact, the contractor hires a golf course architect and a number of specialized subconsultants, and they collaboratively design and build the golf course (with the help of specialized subcontractors) (also known as Design-Build).

c) A golf course architect is hired by the owner as a single point of contact and the golf course architect hires shapers and laborers to build the golf course (with the help of specialized subconsultants and subcontractors) (also known as Architect-Led Design-Build)

Regardless of methodology, the best finished product is achieved when the golf course architect takes the time to thoroughly understand the site and when the entire project team is flexible and incentivized to take advantage of opportunities that arise once construction has begun.

Dr. Alister MacKenzie, a legendary architect of the “Golden Age”

From Old Tom Morris to Tom Doak (and beyond)

Dating back to the 1850’s, when a golf pro and “keeper of the green” named Old Tom Morris began laying out links golf courses on the sandy coasts of Scotland and Ireland, golf course architects have employed many methodologies to bring their ideas for golf course routings and strategic features from brain to ground.

Lacking mechanical power, early golf course architects (often golf course superintendents or professional golfers who moonlighted as amateur golf course architects) employed a necessarily light touch and very little planning that could best be described as “18-stakes on a Sunday afternoon”.

During golf course architecture’s next distinct era - the “Golden Age” (between the turn of the 20th century and the late 1920’s) – increasingly professional and specialized golf course architects often entrusted their hand-drawn routings, green sketches, and notes to reliable construction supervisors (for example: Alister MacKenzie with associates Robert Hunter, Alex Russell, and Perry Maxwell), who would employ local labor to build golf courses across the United States, Canada, parts of Europe, and Australia.

In the post-World War II era, beginning with Robert Trent Jones in the 1950’s and extending through the 1990’s, large and prolific golf course design firms often employed many design associates to churn out reams of detailed design plans that were built around the world by specialized or general contractors (both experienced and inexperienced with golf) under the supervision of on-site design coordinators.

Finally, the late 20th century and early decades of the 21st century has seen the ascendency of the design-build methodology using less detailed design plans and small teams of empowered and talented architect-shapers with the freedom to improvise a lot of the key design details for the golf course in the field.

All eras and design philosophies have produced great golf courses to go along with the not-so-great: golf courses that exceed the potential of their sites, alongside opportunities wasted. What are the keys to maximizing the potential of a golf course site; commonalities that can apply to any era and any design style? What is the most cost efficient (and, therefore, economically sustainable) method of design and construction today? How is environmental sustainability best achieved? Is there any one answer that is always right?

Know the Land, Understand the Objective

To state the obvious: no two parcels of land are the same. So, the first key to maximizing a site’s environmental and economic potential is for the golf course architect to really get to know the land that they will be working with. A golf course architect will typically start by seeing topography from an aerial or ground survey but must also take the time to understand the characteristics of the site that can’t be learned by studying a two dimensional plan - where are the best long views? What is the quality of the existing native vegetation and what plants must be protected or salvaged at all costs? What’s on the other side of that property boundary (and what’s likely to be there in the future)? What raw materials does the site offer in abundance (sand, rock, water, clay) and how can these materials be used (rather than having to import other materials)? Where does the surface water drain? Are there any unique landscape, topographic, or historic features? How can the site’s existing habitats and biodiversity be best protected or restored and enhanced? How can the golf course best serve its local community? The list goes on…

Some sites will reveal themselves to the golf course architect immediately while others will require weeks, months, or even years of careful study. Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw famously spent more than two years traversing 8,000 acres near Mullen, Nebraska before eventually finding 136 (!) “very good” golf holes. They narrowed that down to their favorite 18-hole routing and built the Sand Hills Golf Club in 1995 - and it is still one of the top-ranked golf courses in the world.

Even on a site that is seemingly mundane with few to no qualities of note (e.g. a capped landfill or otherwise degraded site), there is still something to be learned. The golf course architect and owner/developer must honestly consider whether such a site will require an expensive and character-changing transformation just to create an average golf course, and whether or not that course can be financially and environmentally sustainable over the long-term.

The bottom line is that getting the best golf course out of any given site isn’t possible without a thorough understanding of the land. It is imperative that the golf course architect devote as much time as is necessary to reach this understanding.

Sustainable Design Best Management Practices

Some core principals of sustainable golf course design (from the GCSAA Best Management Practices):

Proper planning will minimize expenses resulting from unforeseen construction requirements. Good planning provides opportunities to maximize/integrate environmentally favorable characteristics into the property.

Design the course to minimize the need to alter or remove existing native landscapes. The routing should identify the areas that provide opportunities for restoration.

Design the course to retain as much natural vegetation as possible. Where appropriate, consider enhancing existing native vegetation through the supplemental planting of native vegetation/materials next to long fairways, out-of-play areas, and along water sources supporting fish and other water-dependent species.

Design out-of-play areas to retain or restore existing native vegetation where possible. Nuisance, invasive, and exotic plants should be removed and replaced with native species that are adapted to that particular site.

Plan Thoroughly, But Remain Flexible

Armed with an intimate understanding of the land, the golf course architect can now begin work on the design. At the end of the 19th century, that might have meant showing the local shepherds where to release the sheep and telling the “keeper of the green” where to cut holes in the flat areas that would be serving as putting greens. Some famous early golf course architects prepared only stick routings and rough conceptual green sketches for the greenkeepers that they’d be leaving behind to maintain the golf course.

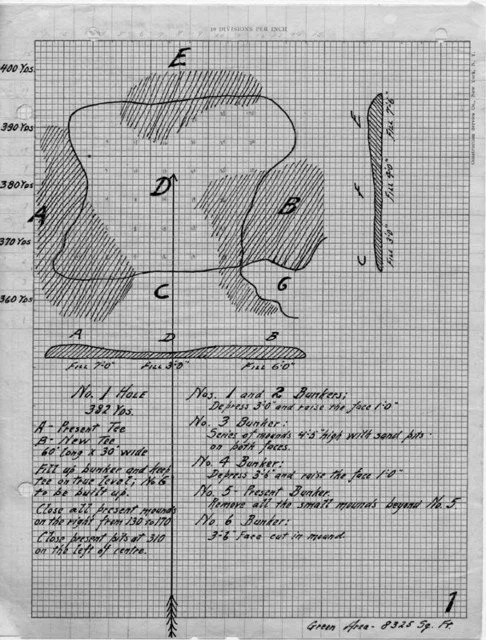

During the “Golden Age” of golf course architecture, many of the most highly regarded golf courses were built by hands-on designers who spent a significant amount of time on-site personally supervising the construction (George Crump’s obsessive approach to building the Pine Valley Golf Club is one well-known example). Due to the constraints of travel and depending on how many commissions they had at any given time, some of the more prolific golf course architects had a large portion of their more distant work built by trusted associates from plans and notes only. Examples include Donald Ross, who is credited with more than 400 golf course designs across the United States, and Dr. Alister MacKenzie, who designed golf courses throughout the UK, the US and Australia, in an era before widespread commercial flight.

A green design by Donald Ross

Following the Great Depression and the Second World War, as economies recovered, travel became faster and safer, and design firms grew larger and took on more work. Many golf course architects in this era felt it was necessary to prepare ever more detailed plans and specifications so that their ideas wouldn’t be lost in translation, since it would be their associates and (potentially inexperienced) contractors who would actually be building the golf courses. Shielding themselves from liability in an increasingly litigious society was another good reason for a golf course architect to prepare very detailed construction documentation. The downside of this was that the contractors would bid the jobs as if the plans were sacrosanct. Effectively this meant that, once construction began, any improvements to the design that were discovered in the field were likely to become, at best, a negotiation and, at worst, an expensive change order. With differing goals and incentives, the golf course architect-golf course builder relationship was often adversarial and left little room or appetite for on-site improvisation.

Today, in an era when personalization and artisanal small-batch production has become more common and desirable throughout the economy, it is once again common to see golf course architects produce less detailed plans that provide the “bones” of the design but allow the golf course to be fleshed out in the field by the golf course architects themselves with the help of their shaper-design associates.

More Specific Versus Less Specific Design Documents (Design-Bid-Build Versus Design-Build)

Design-bid-build and design-build are the two most common project delivery methods used in golf course construction today. A project that is design-bid-build is divided into separate phases: first, the owner/developer hires a golf course architect to complete a detailed design and specifications; next, contractors submit bids based on the completed design; finally, the selected contractor constructs the project.

This approach separates the design and construction responsibilities, often leading to a longer timeline but providing clear checks and balances, with the golf course architect often hired to represent the interests of the owner/developer during construction by overseeing the work of the contractor. Competitive bidding between contractors may lead to initial cost savings but the specter of change orders and delays can disincentivize deviation from the detailed design.

In contrast, design-build projects integrate both design and construction services under a single contract and entity. This means the contractor and golf course architect work together from the project's outset, which can streamline communication, reduce project duration, and potentially lower costs through innovation and value engineering. However, it may offer less oversight for the owner compared to the more segmented design-bid-build process and it can be argued that the golf course architect is no longer strictly representing the interests of the owner/developer (can be more incentivized to make the job profitable for the contractor) and thus has a conflict of interests.

Many of the highest-profile golf course architects today use an architect-led design-build methodology, where the golf course architect prepares less detailed plans and hires or employs trusted design associate-shapers to do a lot of the detailed design in the field. Specialized subcontractors are typically hired separately by the owner/developer for e.g. bulk earthmoving, drainage, and irrigation installation at the direction of the golf course architect and/or subconsultants working alongside the golf course architect, such as a civil engineer, an agronomist, and an irrigation designer. Ultimately, this puts all of the responsibility for the coordination of the project on the golf course architect and can lead to scheduling and budget efficiencies and the flexibility to value engineer and innovate during construction.

However, publicly funded projects (which are often required to be competitively bid (for maximum transparency, objective contractor selection, and easiest cost comparison)), and projects that require strict budget control and where the developer/owner has a well-defined scope that can’t deviate greatly, are still best built using the design-bid-build contract structure.

It’s important to note that, no matter who coordinates or executes the construction, the best finished product will always have allowed for some flexibility and on-site discovery. Even exceedingly detailed plans and specifications cannot anticipate all the issues and opportunities that will be encountered once construction has begun. That is why the golf course architect must be present (or appoint an empowered associate who can be on-site when they are not) and flexible enough to make changes to the design in the field (within the constraints of the client’s budget and schedule). This way, when opportunity or ambiguity inevitably arises, decisions can be made quickly that take advantage of these opportunities while remaining consistent with the overall ethos of the design.

The Relationship Between the Golf Course Architect and the Shapers

At face value, the shaping that happens after bulk earthwork is simply a further refinement in the realization of the golf course architect’s design. It is a process that often uses smaller machinery to achieve a closer-to-finished form. However, in reality, the rough and fine shaping phases (also known as feature shaping because that is when greens, tees, bunkers, and fairways take form) are when the personality of the golf course finally begins to shine through.

Bulk Earthwork at Cabot Links, Nova Scotia

Therefore, one of the keys to maximizing the potential of the golf course is the relationship between the golf course architect and the shapers. If the golf course architect is not doing all of the shaping personally, then they will have to put a certain degree of faith in the shapers (regardless of whether they work directly for the golf course architect, the contractor, or are maintenance staff on loan) to understand and buy-into their vision for what the finished golf course will look like and how it will be played. A big part of the golf course architect’s job is to figure out how to communicate their vision so that every one of the machine operators is on the same page.

When the shapers are employed by the general contractor and are not as familiar with the style and preferences of the golf course architect, the golf course architect may need to produce very detailed plans and provide regular supervision to ensure that their vision is achieved. When the shapers are employed by the golf course architect (in the case of an architect-led design-build job), the golf course architect may be more comfortable giving the shapers some leeway, knowing that they have a shared history and understanding of the golf course architect’s vision for the project. In both cases, the best results are achieved when the golf course architect is frequently present on-site to keep everyone moving in the same direction.

Whether working for the general contractor or the golf course architect, the very best shapers are artistic, independent, efficient, and have a thorough understanding of strategic theory learned by studying the world’s great golf courses. In an ideal situation, the golf course architect and the shapers can have an open and honest dialogue throughout the project, continually updating and refining the golf course architect’s preliminary ideas, while staying within the boundaries and consistent with the golf course architect’s overall vision (and the project budget). In addition, the shapers must be efficient enough to do this without delaying the progress or significantly affecting adjacent work by other contractors and subcontractors, such as the crews installing drainage and irrigation.

What’s the most cost-effective way? What will yield the best golf course? What will lead to the greatest environmental and economic sustainability?

Ultimately, the best way to design and build a golf course is dictated by the complexity of the site and the project, the size of the budget, and what the owner is trying to achieve. However, it is always the golf course architect’s responsibility to understand the site, to clearly and consistently communicate their design vision to whoever is doing the work, and to be open and available to make changes as new information becomes available. Regardless of who is building the golf course or how it is being built, the golf course will only approach its full potential with the golf course architect’s full attention.

We at Sustain Golf believe that thorough planning, availability, and flexibility will inevitably translate into greater harmony with nature, more collaboration with stakeholders, and opportunistic cost savings.

Contact Sustain Golf for more information!

We firmly believe that common sense sustainable design, construction, and maintenance practices are the keys to the long-term outlook for the game of golf. We at Sustain Golf aspire to be on the leading edge of applying sustainability concepts to golf course design and construction.

We would be happy to answer any questions that you might have about sustainable golf course design, maintenance, and construction. Visit us at www.sustaingolf.com or contact us at the following email address for more information: matt@sustaingolf.com

Up Next:

Step 3: The Importance of a Consulting Agronomist

Sustain Golf is a sustainability- and accessibility-focused golf course design company. We have the breadth and diversity of experience and knowledge to offer a full suite of golf course design, construction, and consultation services, from first concept to opening day and into operations on your new or remodeled golf course.

References:

Alister MacKenzie Photo Credit: Bettmann Corbis Archive

Cutten, Keith (Edited by Paul Daley), The Evolution of Golf Course Design. Victoria, Australia: Focus Print Group, 2018.

Hurdzen, Dr. Michael J. Golf Course Architecture: Design, Construction & Restoration. Chelsea, MI: Sleeping Bear Press, 1996.

Golf Course Superintendents Association of America. (2023). Best Management Practices. Planning Guide & Template. GCSAA Foundation. https://www.gcsaa.org/docs/default-source/environment/bmp-planning-guide_2023_print_final.pdf

Peer Review:

Excerpts from an essay by Schiffer, Matthew & Cutten, Keith, (2019). Compare and Contrast: Design-Build vs Contractor Model of Golf Course Construction

Joe Hancock, Hancock Golf LLC

Dr. Keith Duff, former UK government wildlife agency Chief Scientist, current Golf Environment Consultant